+

Lord Jesus Christ, whose Will all things obey: pardon what I have done; grant that I, a sinner, may sin no more!

Lord, I believe that though I do not deserve it, You can cleanse me from all my sins. Lord, I know that man looks upon the face, but You see the heart.

Send Your Spirit into my inmost being, to take possession of my soul and body. Without You I cannot be saved; with You to protect me, I may long for Your Heaven.

Now I ask for Your salvation. I ask You for wisdom, deign of Your great goodness to help and defend me. Guide my heart, Almighty God, that I may remember Your Presence day and night.

++ Amen ++

Widely known as the “bustan al-rohbaan” (The Monks’ Garden) in the Coptic Catholic Church, is not a single book, rather a collection of sayings and stories written by and of the Desert Fathers of Egypt.

These are from a book edited by Sister Dr. Benedicta Ward, SLG of Sisters of the Love of God at Incarnation Monastery in Oxford, England.

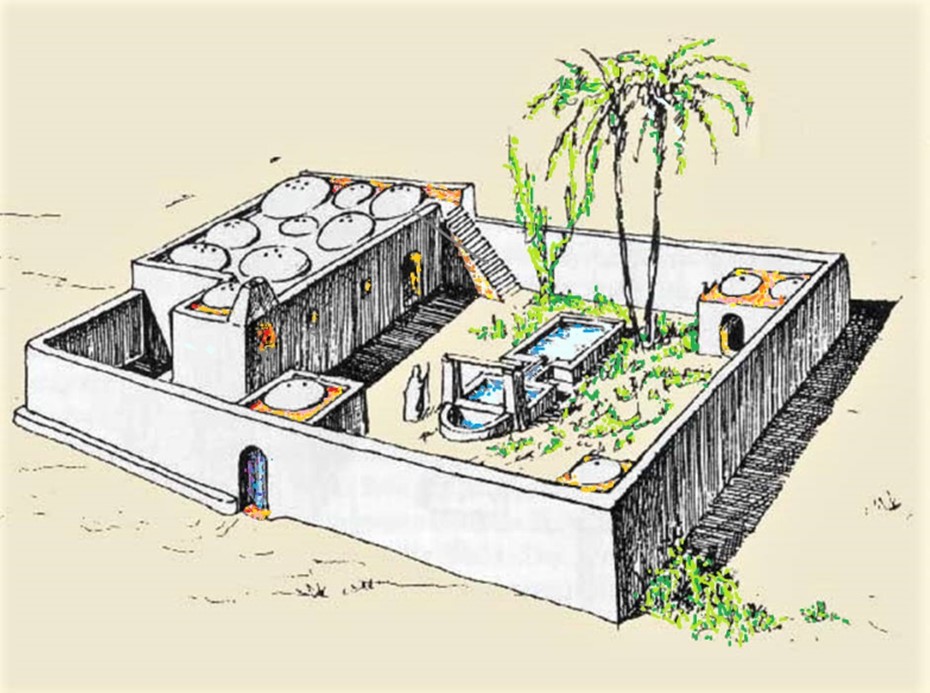

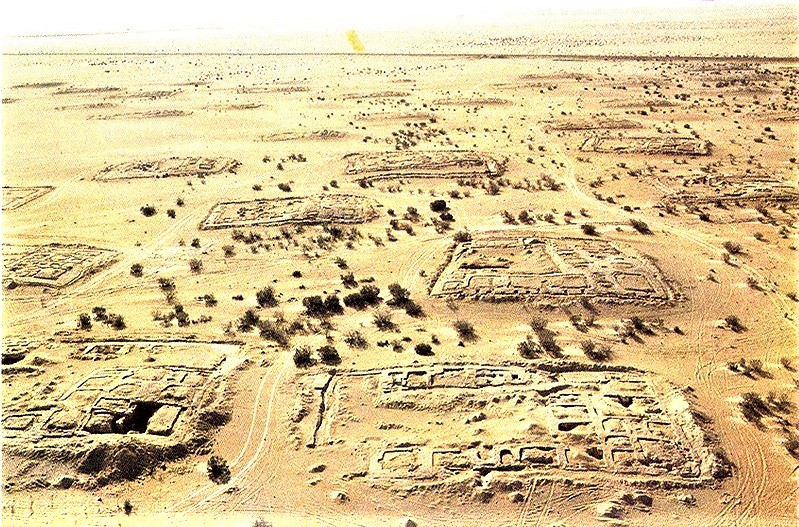

In the 4th Century AD, an intensive experiment in Christian living began to flourish in Egypt, Syria and Palestine. It was something new in the Christian experience, uniting the ancient forms of monastic life with the Gospel. West of the Nile Delta was the Nitrian Desert, a wasteland, a dry lake area which only contributed salts for embalming the dead. In Egypt this solitary movement was so pop- ular that both the civil authorities and the monks themselves became anxious. As for the officials of the Empire, so many thousands were following a way of life that excluded both military service and payment of taxes, but also the monks, as the large number of inter- ested tourists threatened their solitude.

The first Christian monks tried every kind of experiment with the way they lived and prayed, but there were 3 main forms of monastic life: there were the hermits who lived alone; there were monks and nuns living in communities; and in Nitria and Scetis there were those who lived solitary lives, but in groups of 3 or 4, often as disciples of a master. For the most part they were simple people, peas- ants from the villages alongside the Nile, though a few were well educated.

“A beginner, who goes from one monastery to another, is like a wild animal who jumps this way and that for fear of the halter.”

Visitors, who were impressed and moved by the penitential life of the monks, imitated their way of life as far as they could, and also provided a literature that explained and analyzed this way of life for those outside it. However, the primary written accounts of the monks of Egypt are not these, but records of their words and actions by their close disciples. Often, the first thing that struck those who heard about the Desert Fathers was the negative aspect of their lives. They were humble people who did without: not much sleep, no baths, poor food, precious little water or company, ragged clothes, hard work, no leisure, absolutely no sex, even in some places, no church either – a dramatic contrast of immediate interest to those who lived out the Gospel differently.

But to read their own writings is to form a rather different opinion. Although the literature produced among the monks them- selves is not very sophisticated; it comes from the desert, from the place where the amenities of civilization were at their lowest point, where there was nothing to mark a contrast in lifestyles; and the emphasis was less on what was lacking, but more on what was present. The outsider saw the negations; disciples who encountered the monks through their own words and actions found, indeed, great austeri- ty and poverty, but it was neither unbelievable nor complicated. These were simple, practical people, not given either to mysticism or to theology, living solely by the Word of God, for the love of the brethren and of all creation, waiting for the coming of the Kingdom with eager expectation, using each moment as a step in their pilgrimage of the heart towards Christ.

From this deep desire for the Kingdom of Heaven came power to dominate their whole lives so that they lived without things: they kept silence, for instance, not because of a proud and austere preference for aloneness, but because they were learning to listen to some- thing more interesting than the talk of men, that is, the Word of God. These were rebels, the ones who broke the rules of the world – which say that property and goods are essential for life, that the one who accepts the direction of another is not free, that no one can be fully human without sex and domesticity. Their name itself, anchorites, means rule-breakers, the ones who do not fulfill their public duties. In the solitude of the desert they found themselves able to live in a way that was hard but simple, as true Children of God.

Abba Milos of Belos said, “Obedience responds to obedience. When someone obeys God, then God obeys his request.”

The literature they have left behind is full of a good, perceptive wisdom, from a clear, unassuming angle. They did not write much, most of them remained illiterate; but they asked each other for a “word,” that is, to say something to recognize the Word of God, which gives life to the soul. It is not a literature of words that analyze and sort out personal worries, or solve theological

problems; nor is it a mystical literature concerned about presenting prayers and praise to God in a direct line of vision; rather,

it is oblique, unformed, occasional, like sunlight glancing off a rare oasis in the sands.

Abba Antony said, “Our life and our death are with our neighbor. If we gain our brother, we have gained our God; but if we scandalize our brother, we have sinned against Christ.”

Abba Nilus said, “The arrows of the enemy cannot touch one who loves silence; but he who moves about in a crowd will often be wounded.”

–Sister Dr. Benedicta Ward, SLG