Ancient Desert Spirituality

ANCIENT SPIRITUAL DIRECTION

PART 1

“DO not be afraid to hear about virtue, and do not be a stranger to the term. For it is not distant from us, nor does it stand external to us, but its realization lies within us and the task is easy, if only we will receive it.”

For the Lord has told us before, ‘The Kingdom of God is within you.’ The only thing goodness needs, then, is that which is within the human soul and mind.”[1]

‘It’s realization lies within us’ – this conviction that the kingdom of God is to be discovered within the human heart lies at the center of the spiritual teaching of the desert.

The 4th century in Egypt saw the invention of Christian monasticism and it produced some of the finest texts ever written about conversion of the heart, that is to say, of the whole person, within the Tradition of the Gospel.

The whole life of the monks was a training, not a search for ‘illumination’ – but a training, an ascesis, both for, and in, the life of the kingdom of God.

The perspective of things has subtly changed in the clear air of the desert, the ‘huge quiet’ of the Nitrian Desert, Scetis, and the Cells. They said: There is no labor greater than that of Prayer to God.

For every time a man wants to pray, his enemies, the demons, want to prevent him, for they know that it is only by turning him from prayer that they can hinder his journey. Prayer is warfare to the last breath! And when Abba Sisoes was dying, even though his face ‘shone like the sun,’ he said, ‘I do not think I have even made a beginning yet!’

In this lifetime of conversions, the monks found that they needed the assistance of others, not only in the practical matters of life in the desert, though that was of great importance to them, but in the inner ways of the heart.

It would be an anachronism to talk about ‘spiritual direction’ among the desert fathers; they were very clear that the process of turning towards God was a matter of the spirit and the body together, and that this spiritual direction was given only by Christ. Any help they asked or received from one another – was with this in mind: ‘we ought to live as having to give account to God for our way of life – every day.’ “They are like the dogs who hunt hares, the one who has seen the hare: pursues it until he catches it, without being concerned with anything else. So it is with him who seeks Christ as his Master: ever mindful of the Cross, he cares for none of the scandals that occur, until he reaches the Crucified.”

Their ‘training’ is a process of turning from the bonds and limitations of the Self – into the Freedom of the Sons of God, and any words spoken between them are for this end: the attainment of that stillness – in which the Spirit of God alone guides the monk.

For this reason, they are very sparing with their words, and one should not be misled that the records of the desert come to us primarily in the form of conversations. They, in fact, are sentences remembered over many years and grouped together from several periods and areas.

It is these fragmentary words which lead into the atmosphere of the desert more than the literary constructions created later by John Cassian in his Institutes and Conferences.

More truly of the’ desert is the story of Abba Macarius and the two young strangers who came to him for guidance. He showed them where to live and left them alone for 3 years before he inquired any further about them; or of Abba Sisoes who decided that his own part of the desert was becoming crowded, so went to live on the mountain of St. Antony; there, he said to a brother, he lived peacefully for ‘a little time.’ The brother asked how long this ‘little time’ of total silence and solitude was. He replied, ‘72 years!’ Against this background of the ‘ages of quiet without end,’ the timelessness and silence of the desert, is it possible to say anything about their assistance of each other—in their lives of conversion?

It would be wrong to look for a coherent program of spiritual direction in such texts, but it is possible to see their expectations and experiences through some of the Sayings. Some practical ways of learning metanoia emerge from the texts, virtually the same for both the lone hermits and the communal cenobites. Certain ‘sayings’ reveal the basic understanding of training in the monastic life in the desert. It is worth recalling the conviction of the desert fathers that the life of salvation is for all, not the exclusive preserve of monks, a theme which was always there, best expressed: God is for all those who chose him, life for all, salvation for all, faithful, unfaithful; just, unjust, good, bad, etc. A spiritual direction – which comes from God at the very beginning of Conversion – is the first and perhaps the most vital of the ways of spiritual understanding in this tradition.

While still living in the palace, Abba Arsenius prayed to God in these words, ‘Lord, lead me in the way of salvation!’ A voice came saying to him, ‘Arsenius, flee from men and you will be saved.’ Having withdrawn to the solitary life, he made the same prayer again, and he heard a voice saying to him, ‘Arsenius, flee, be silent, pray always, for these are the sources of sinlessness.’

These sayings of Arsenius, the most famous of the Fathers of Scetis contain several things that are of the essence of the spirituality of the desert. There is the desire for one thing only, Salvation, with the ideal of Constant Prayer for the whole of Life. Always there is in some form this ‘voice’- this command from God. In the case of Arsenius, it is a direct answer to him when he prayed. For others it is mediated through one of the many ways in which a Christian can expect to hear the Will of God. Antony the Great, the Father of Hermits, heard this Gospel read in church, ‘If you will be perfect, go, sell all you have, give to the poor and Come Follow Me and you will have treasure in heaven.’ This time, those familiar words from the scriptures pierced his heart. Antony immediately left the church and gave to the townsfolk the property he owned and devoted all his time to ascetic living. After a while, he went farther into the desert. A practical Action, then Flight, into Exile, a going away from the familiar world of the village, as Arsenius fled from the palace of the Emperor. For Pachomius, Father of Cenobites, it was the Charity of Christians that moved him, to leave his life as a soldier and go into the solitude of the desert. For Apollo, a rough Coptic peasant, it was horror of his own sin that caused him to flee, followed by a further piercing of his heart when he came near Scetis and heard the monks repeating a Psalm. ‘So he passed all his time in prayer, saying “I as man have sinned; do thou as God, forgive!”

–Sr. Benedicta Ward, SLG Part II Follows

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

ANCIENT SPIRITUAL DIRECTION

PART 2

“This pattern of being moved by the action of God first, of leaving a familiar place, going away – giving of oneself to the action of God in silence and solitude is the gateway to Desert Prayer and Conversion of heart. What follows until death is the hard work of becoming a new man in Christ: one of the Fathers asked Abba John the Dwarf, “What is a monk?” And he said, “He is toil. The monk toils at all he does. That is what a monk is.” This ‘toil’, this ‘hard work’ lasted a lifetime. And the spiritual direction had to be constantly followed and kept clear. In this task, the monk had 3 assets: first was his cell; then the scriptures and the last was an old man, a father, a mentor, as a point of reference in all he undertook. The Desert Sayings are full of references to the cell of a monk as the place, which in itself, directed the monk’s life. The flight into the desert leads to a place of stability: ‘Just as a tree cannot bring forth fruit if it is always being transplanted, so the monk who is always going from one place to another is not able to bring forth virtue.’ The first action of the newcomer to the desert was either to build a cell for himself, a simple one-roomed hut, or to join an established monk in his cell. The idea of staying in the cell is stressed repeatedly: ‘Go, sit in your cell, and give your body in pledge to the walls of your cell, and do not come out of it.’ A further example: ‘Once a brother came to Scetis to visit Abba Moses and asked him for a word. The old man said to him, “Go, sit in your cell – and your cell will teach you everything.”

Why is it that they saw this stability in the cell as vital in their spiritual training? It was because they could learn there, and there only, that God exists, because if God is not here and now, in this moment and in this place, He is nowhere. To remain in the cell was to stay at the center of human suffering and discover that God is there, that at the center there is life, salvation, light and not darkness. They said, ‘the cell of a monk is the furnace of Babylon, but it also is where the 3 children found the Son of God; it is as the pillar of cloud, and where God spoke to Moses.’ The cell was the place of hard work: Abba Sarapion once visited a celebrated recluse who lived always in one small room and he asked her, ‘Why are you sitting here?’ She replied, ‘I am not sitting. I am on a journey.’ So the first teacher of the monk was God; the second was his cell. Within the cell, the monk had one sure guide and often it was the same guide that began his conversion, the scriptures. The language of the writings of the desert was so formed by meditation on the scriptures that it is near impossible to say where quotation ends and comments begin. The thought of the monk was shaped by constant reading and learning by heart the text of the Bible, and in particular by the constant repetition of the Psalms in the cell.

Later generations used also the constant prayer of the Name of Jesus, and while this form of words (‘Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the Living God, have mercy upon me, a sinner!’) is not found in the Apophthegmata, the idea of continual prayer by using a set form of words from the Psalms was central to it. The combination of attention to God, the stability of the cell and the meditation on the scriptures is found in a saying of Abba Antony:

“Always have God before your eyes; whatever you do, do it according to the testimony of the holy scriptures; in whatever place you live, do not easily leave it. Keep these 3 precepts and you will be saved.”

Epiphanius of Cyprus urged the reading of the scriptures for his monks: ‘Reading the scriptures is a great safeguard against sin. Ignorance of the scriptures is a precipice and a deep abyss.’ But for simple Coptic monks the scriptures were more than this. They were bread of heaven on which they fed as often as they could, and as literally as possible. The breaking of the bread of the Scriptures was to them the bread of life, and there are stories of monks going for many days without food being fed by this bread of heaven. Abba Patermuthius, a robber, went after his conversion into the desert for 3 years, having learnt only the first Psalm; he spent his time there ‘praying and weeping, with wild plants sufficient for his food’; when he returned to the church, he said that God had given him the power to recite all the scriptures by heart. The fathers were astonished at his “high degree of ascesis’ and quickly baptized him as a Christian. Meditation on the Scriptures, the main guide for the monk, is here presented as a Sacrament; not an intellectual study, but a free gift of God as the bread of life in the wilderness, even for one not yet baptized.

Part 3 Follows —Sr. Benedicta Ward, SLG

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

ANCIENT SPIRITUAL DIRECTION

PART 3

Meditation on the Scriptures, the main guide for the monk, is here presented as a Sacrament; and not as an intellectual study, but as free gifts of God and, as the bread of life in the wilderness, even for one not yet baptized.

This consideration of the scriptures as a sacrament leads to the next channel by which the monk learned the lessons of the desert, that is, by the words of a father. The most frequent request of one monk to another was ‘speak a word to me,’ the monk was not asking for information, or instruction. He was asking, as with the Scriptures, for a Sacrament. The ‘word’ was not to be discussed, analyzed or disputed in any way; at times, it was not even understood; but it was to be memorized and absorbed into life, as a sure way towards God. Pachomius said that if someone asked for a ‘word’ and you could think of nothing to say, you should tell him a parable of some sort and God would still use it for his salvation.

There are stories of monks who would go to live with an old man, and find that he would never give them instructions or orders; they could imitate him if they wished; and if he spoke, the words were for them to use, not debate.

A brother asked a monk what he should do, because he always forgot whatever was said to him, and the old man used the image of a jug which is frequently filled with oil and then emptied out: ‘So it is with the soul; for even if it retains nothing of what it has been told, yet it is purified.’ It was not the words of the father that mattered in themselves. Nor were his personality and treatment of the disciple central, a point made very clearly in a story about Abba Ammoes:

At first Abba Ammoes said to Abba Isaiah (his disciple), ‘What do you think of me?’ And he said to him, ‘You are an Angel, father!’ Later he asked, ‘And now, what do you think of me?’ He replied, ‘You are like Satan! Even if you say a good word to me, it is like Iron!’

The father of a monk in the desert was not a guru, nor was he a master; he was a father, so several things followed from this. The abba did not give ‘spiritual direction;’ if asked, he gave ‘a word’ which would become a sacrament to the hearer.

The action of God was paramount and the only point of such ‘words’ was to free the disciple to be led by the Spirit of God, just as the abba himself would. In the desert there could only be one father to a disciple, and even when he died, he was still the father of his sons. There was no need to change fathers, or to find a new one, if one died. It was a lasting and permanent relationship. In such a relationship, Tradition was passed on by life, as well as by word; those who had already been a certain way into the experience of the monastic life must be able to become this channel of grace for others. But, the aim was always for the Abba to disappear. The real guide was the Holy Spirit, Who would be given to those who learned to receive Him. Moreover, in this relationship, it was almost always the disciple who asked for a word, not the Abba who offered one. The lesson to be learned, (the ‘Sayings’ are full of stories of puzzled newcomers – who found it incomprehensible not to be instructed) was that each one had to learn to receive the gift of God by himself; and it was precisely in learning this, that the disciple began to pray. There was no set of instructions, no pattern, for the monk; just some simple external ways of living, the word of the Scriptures and, if requested, the sacrament of the words of a fellow monk.

It was, and remains, a hard way, and in order to use it properly, the disciple needed to see this as a personal Crucifixion with Christ, wound against wound, so that the Life of the Spirit might be truly given.

A brother asked an old man, ‘How can I be saved?’ The latter took off his habit, girded his loins, and raised his hands to heaven, saying, ‘So should the monk be: denuded of all things in this world, and crucified. In the contest, the athlete fights with his fists; in his thoughts, the monk stands, his arms stretched out in the form of a cross towards heaven, calling on God. The athlete stands naked when fighting in a contest; the monk stands naked and stripped of all things, anointed with oil, and taught by his master how to fight. So God leads us onward to victory.’

The necessary abdication of the selfish center of man, which John of Lycopolis saw as a serpent deeply coiled round the heart of men, so deeply embedded that it was impossible to remove it by oneself, which demanded the monk’s full attention, daily and in minute detail – for his whole life.

The literature of the desert is not about lofty visions or spiritual experiences; it is about the long process of the Breaking of Hearts. The monks defined themselves as sinners, as penitents, who would always need mercy. There are, in this tradition, many things that resulted from this approach. One of them was that suppleness of spirit, which breaks through the stiff lines of self-determination and self-righteousness, makes the soul supple and pliable to receive, as they would say, the impress of the Spirit, as a signet upon wax. One of the ways of discovering if this process was continuing – lay in the acceptance of the Abba by the disciple as the one who discerned all realities, against the evidence of the senses; as the one who knew what should be done, against the limited understanding of obligations; who knew what was ever possible, against the dictates of common sense. These words, actions, or opinions did not matter in themselves; what concerned the monk was – his ability to listen and obey. Part 4 Follows -Sr. Benedicta Ward, SLG

This life of discovery of the power of the cross in a human life, lived practically and realistically, without notions and theories, produced three ‘signs.’

Part 4 Follows – Sr. Benedicta Ward, SLG

| **************************************************************************** |

ANCIENT SPIRITUAL DIRECTION

PART 4

What concerned the monk was – his ability to listen and obey. This life of discovery of the power of the Cross in a human life, lived practically and realistically, without notions and theories, produced 3 ‘Signs.’

First, the sign of Tears: as it was said of Abba Arsenius that he wept so much that ‘he had a hollow in his chest channeled out by the tears that fell from his eyes all his life’; and the young monk Theodore, the favorite disciple of Abba Pachomius, wept so much that his eyesight was endangered. Tears signified the Baptism of Repentance, rather than superficial emotional disturbance, in this Tradition, and were often associated with meditation on the Passion of Christ. One old man asked another, ‘Tell me where you were . . .’ and he said, ‘My thoughts were with St. Mary the Mother of God as she wept by the cross of the Savior. I would that I could always weep like that,’ said Poemen to his pupils.

These tears were valued, not ignored or explored; in this theme of weeping and allowing others to weep there is a vital element in the ‘spiritual direction’ in the desert. It is this: the monk undertook a life of ascetic prayer and it was held that this was what he most desired; so that when he wept, or groaned, or had to fight against temptations, in fact, whenever he suffered profoundly, and continually, he was allowed to do so, indeed, he was encouraged by others, and especially by his Abba, to stay at this point of pain in order to enter into the only true healing, which is God. When Moses the Black, one of the most attractive of the monks of Scetis, was tempted to fornication, he came to Abba Isidore and told him he could not bear the temptation. Isidore urged him to return to his cell and continue the battle, but he said, ‘Abba, I cannot’; so Isidore then showed him the ‘multitudes of angels shining with glory’ who were fighting within the monks against the demons, and with this assurance, but with no alleviation of the suffering to be endured, he returned to his cell in peace.

The women of the desert seem to have been as clear about this as the men: ‘It was said of Amma Sarah that for 13 years she waged war against the demon of fornication. She never prayed that the warfare should cease, but she said, “O God give me strength for the fight!”

This concentration upon the value of suffering in the light of the cross of Christ leads to the 2nd Sign which was seen as a mark of authenticity in the lives of the monks: Charity.

Insofar as the monk truly found himself ‘crucified with Christ,’ so far did he receive the Holy Spirit, and display in his life the Gifts of the Spirit of God. The charity of the monks, their warmth, their unaffected welcome of each other and of strangers, their practical care of one another were as famous as their asceticism; the other side of their pain was their joy. This was not the kind of pleasure which is an alternative to and an escape from suffering nor is it an exploitation of others, but a realization of that ‘Christ between us’ that gives deep and true relationship. It is the life of the kingdom, of the 2nd Adam, of man restored to paradise, and though at no moment did they forget that this was only so through the cross at the center of their lives, the result was not gloom, but radiance. The most striking result of this spirituality is closely connected with the reserve of the elder fathers about giving orders or rebukes to the newcomers: they did not judge one another in any way. It was said of Abba Macarius that he ‘became as it is written a god upon earth, because just as God protects the world, so Abba Macarius would cover the faults that he saw (as if he did not see them), and those which he heard (as though he did not hear them).’

This freedom to live increasingly in the power of the Spirit points to the 3rd sign of desert spirituality: there is a concern for unceasing prayer in this tradition, not as a support to works – but as the life of the monk, and this is often expressed in terms of ‘the prayer of fire.’ The end and aim of the monk was to be so open to the action of God that his life would fill each moment of the day and night.

Prayer was not a duty or obligation, but a burning desire. The older monks never ‘taught’ prayer; they prayed and the newcomers could find in their prayer a way for them to follow. Abba Joseph said to Abba Lot, ‘You cannot become a monk – unless you become like a consuming fire’, and when Abba Lot asked what more he could do beyond his moderate attention to prayer each day, ‘the old man stood up and stretched his hands towards heaven, his fingers became like ten lamps of fire and he said to him, If you will, you can become ALL Flame”‘

The search for God in the deserts of Egypt in the 4th Century came to an end with the devastation of Egypt in 407AD, though there is at present a revival of this way of life in the monasteries of the Wadi al’Natrun, which is a continuation as well as a revival. What remains for us are the written records of their lives. Certain documents of the early generations, a few letters and brief sayings of the fathers provide a clue to the lives they lived; the accounts of their actions and their conversations with visitors also survive, in the Institutes and Conferences of John Cassian, the History of the monks of Egypt, and the Lausiac history. The theology of the monastic life of Egypt was first analyzed by Evagrius Ponticus and John Cassian.

In Palestine and in Syria, other men experimented with monastic life and left other records, most notable of which are the Letters of Barsanufius and John. But it is in the sayings of the fathers, the collections of their words, that the spirit of the desert can best be found. They themselves began to commit their words to writing and many of them regretted that this had already become necessary even in Scetis and Nitria.

The first fathers, they said, lived practical and realistic lives, whereas the 2nd Generation seemed to them to rely upon that distorting mirror, the written word, more and more. Abba Poemen asked Abba Macarius, weeping, for a word, but he said, ‘What you are looking for – has disappeared among monks!’

Perhaps the essential message of the desert lies precisely there: it is not in reading or discussing, or even in writing articles, that the life of the soul is to be discovered, nor is it in the advice of anyone else, however experienced. It lies in the simplicity of Antony the Great, who, hearing the Gospel read, went and did what he had heard, and so came, at the end of his life, to a point of discovery of the Kingdom of God within himself – that he could say, ‘I no longer fear God; I love him!’

– Sr. Benedicta Ward, SLG

Antony Abbott, the Great................ Pacimonius ................... Abba Agathon........................... Desert Monastery.

Who Were the Desert Fathers?

The Desert Fathers emerged in Egypt. Perhaps as early as the late 200’s AD, these Egyptian Christian men left the pagan cities, the persecutions and the distractions of life to live as hermits in the Sahara Desert. Their purpose was to live a solitary life solely dedicated to God.

Saint Antony the Great

A wealthy, young Christian man, Antony of Egypt (c. 251-356), gave away all his inherited riches and retired to a hut in the desert. His very long and influential life as a hermit precipitated what has been called “the peopling of the desert.”

After his biographer Bishop Athanasius (293-373) published his Vitae Antonii extolling Antony’s life, flocks of Christian men and women came to Egypt to live the anchoritic life exemplified by St. Antony.

A saying of St. Antony: “To those who have an active belief, reasoned proofs are needless and probably useless.”

Soon the desert around Egypt’s major cities was filled with people living in individual cells they had built with their own hands. They wove baskets to sell, formed loose-knit communities and devoted themselves to labor, solitude and prayer. With the blood persecutions over in 313 with the Edict of Milan giving Christians the right to worship, some Christians began to embrace a “white martyrdom” in which the flesh was mortified so that the spirit might live.

Another Egyptian from Thebes named Pachomius (292-348) was one of the founders of modern communal monastic life.

Saint Pachomius

When he was 20, he was imprisoned by the Romans. Local Christians brought him and other prisoners food and other necessities every day. According to Aristides, the 2nd century apologist, Christians typically ministered not only to their brothers and sisters who were in prison for the faith, but to all prisoners as a witness to Christian charity and care:

“(Christians) help those who offend them, making friends of them; do good to their enemies….When they meet strangers, they invite them to their homes with joy….When a poor man dies, if they become aware, they contribute according to their means for his funeral; if they come to know that some people are persecuted or sent to prison or condemned for the sake of Christ’s name, they put their alms together and send them to those in need. If they can do it, they try to obtain their release.” Apology 15

Because of the kindness of Christians to people they did not even know, Pachomius became a Christian when he was released from prison in c. 314. Jesus had said to His followers:

“’For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you visited me, I was in prison and you came to me.’ Then the righteous will answer him, saying, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink? And when did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you? And when did we see you sick or in prison and visit you?’ And the King will answer them, ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.’” Matthew 25:35-40

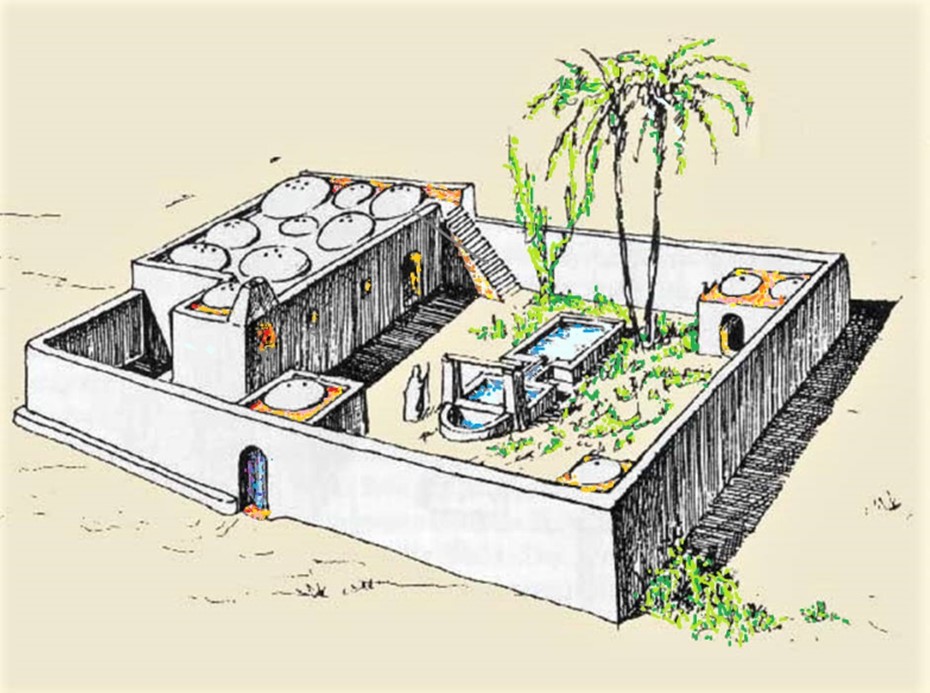

Pachomius felt drawn to the Desert Fathers and built his cell in the desert near St. Anthony. But Pachomius saw that most of the men who desired Anthony’s eremitic life could not live in such solitary isolation. He decided to build 10 to 12 room houses where men could live together in individual rooms and practice, if they so chose, certain mortifications of the flesh such as celibacy, obedience, poverty and/or self-sufficiency. These early monasteries, and soon nunneries, had no Biblical mandates or foundations but were an outgrowth of the human desire to follow God without the normal daily distractions.

Even though there had been monastic groups before Pachomius, he is called the “Father of Cenobitic Monasticism.” “Cenobitic” comes from the two Greek words koinos meaning “common, shared by many” and bios meaning “life.” Pachomius’ “communal living” was the opposite of Anthony’s solitary, hermitic life. The genius was that he had combined the reclusive life of the individual cells with the communal life of corporate meals, work and worship. Pachomius remained monastic his whole life and refused to be ordained as a priest. At his death on May 9, 348 more than 3,000 of his small “monasteries” dotted the Egyptian desert.

1,700 years later there are still 11 Christian Monasteries (Greek monazein meaning “to live alone”) scattered throughout the Sahara Desert in Egypt.

The Desert Fathers and Mothers on Solitude

To the Christian Desert Fathers and Mothers, solitude is not merely a physical state to be contrasted with living among people. Solitude was initially an experimental mode of living due to the harsh environment of the desert, the need for weekly liturgical attendance, and an unregulated (by church authorities) extra-monastic life.

Living as hermits without true precedents was a new psychological expression requiring forethought and self-knowledge. The experiences of the hermits was a process of refining the meaning of solitude and eremiticism with trial and reflection. In this way, their experience parallels that of every solitary seeking the path that the Desert Fathers tread.

Thus, when a young brother asked him to recommend whether to live as a solitary or to stay in the monastery, Abba Joseph of Panephysis replied that whichever state brought him peace was to be preferred, and that if he could not decide even then, it should be based on whichever enabled him to make spiritual progress. This statement fits within the then yet tentative status of eremiticism, as when Athanasius, the biographer of St. Anthony, says of eremiticism that “this was not as yet usual.”

Further, the desert monks realized, as Amma Syncletica puts it:

There are many who live in the mountains and behave as if they were in the town, and they are wasting their time. It is possible to be a solitary in one’s mind while living in a crowd, and it is possible for one who is a solitary to live in the crowd of his own thoughts.

Therefore, solitude had to develop its own prescriptions and techniques every bit as relevant to the solitary as monastic rules to the coenobitic monk. This fruits of this experiment in discovering (on their own, not mandated by anyone) the secrets of successful solitude is precisely what the desert hermits sought to articulate in these early centuries of formative Christianity.

Most solitaries had spent a considerable number of years in a monastic setting, where they saw their lives as inevitably intertwined with their fellows. “Our life and our death is with our neighbor,” said Anthony. “If we gain our brother, we have gained God, but if we scandalize our brother, we have sinned against Christ.”

This sentiment, which summarizes the coenobitic or social mode of life, and which became the standard of Christian living in the West in contrast to the more mystically-oriented Eastern Christianity, was a natural concern even after the same brothers or sisters became desert solitaries. They understood their interrelations to be an opportunity to practice the virtues of patience, compassion, and mutual aid, but without the guardian eye of an abbot.

In the monastery, as Syncletica puts it, obedience was more important than asceticism.

But once outside the monastery, the whole psychology changes. The will must be self-motivated. Emotions must be self-tempered. Every action takes on a kind of spiritual utility.

Anthony notes the change by comparing a monk and a fish: A monk loitering outside his cell or passing time with men of the world is like a fish out of water, in danger of losing inner peace and interior watchfulness. But in solitude there is a different focus, not in losing one’s peace due to physical or human distractions but in getting rid of the physical and human elements altogether. Anthony summarizes it thusly: “Who wishes to dwell in the solitude of the desert is delivered from three conflicts: hearing, speech, and sight.”

Likewise, Poemen notes that coenobitic dilemma: “He who dwells with brethren must not be square but round, so as to turn himself towards all.” But this is a great challenge to a recollected spirituality and to psychological discretion.

Such constant interaction requires an exhaustive exercise of discernment, humility, and a withdrawal from controversy, while at the same time demanding an active and regular participation and cooperation that creates of the personality a necessary if muted extroversion. While it may seem difficult to think of a monastic setting as “extrovert,” the subtle interrelations documented by monks certainly reveal a micro-society every bit as complex as the world.

The solitary may not have or want to marshal forth the psychological resources to function that way. Not that the would-be solitary therefore has all the requisite skills for solitude, either. For successful solitude has its skills and technique, as does a successful coenobitism. Poemen expresses it discretely: “It is not through virtue that I live in solitude, but through weakness; those who live in the midst of others are the strong ones.”

And Abba Lucius concludes: “If you have not first of all lived rightly with others, you will not be able to live rightly in solitude.”

Those who choose Solitude – after a Coenobitic life – often harshly criticized the laxity of the monastery. Perhaps on a psychological level they are overcompensating to justify their chosen — “eccentric” in the eyes of most — way of life. On the larger social and historical level, however, the lives of reformers from Romuald to Francis of Assisi suggest that the critique was not merely psychological. Indeed, criticism of this sort was the impetus of the medieval reform of the Benedictine and Cistercian orders in Europe. With Thomas Merton and others in modern times it continues to present eremiticism as a subtle spirituality.

Conversely, complaints upholding the pure ancient models against the present laxity often sound generational among the Desert Fathers, as when Abba Elias tells his brothers:

In the days of our predecessors they took great care about these three virtues: poverty, obedience and fasting. But among monks nowadays avarice, self-confidence and great greed have taken charge. Choose whichever you want most.

And the critique often involved specific actions, as when Theodore of Pherme criticized monks who, in his presence, drank wine in respectful silence but drank freely nevertheless. “The monks have lost their manners and do not say ‘pardon’.”

Thus a clear motive for many who were to pursue solitude was the insufficiency of not only the world but of those they encountered in the monastery — and, by extension, in the Church at large. Coupling this negative experience with the positive benefits of solitude, the individual was led to the only possible state of life and the need to prepare for it. As the Japanese Zen monk-hermit Ryokan said, “It is not that I dislike people, it is just that I am so tired of them.”

The criticisms by the solitaries appear harsh in terms of morals and behavior of others, but they were not hateful or misanthropic. Indeed, disengagement meant removing the conflict with the world and thereby the spirit of contention that marks all who would want other people to change.

An essential point emphasized by the desert hermits is that social life interferes with spiritual goals. Abba Apphy led an austere life as a monk but could not practice in the same way after becoming a bishop. Was it a withdrawal of God’s grace? he wondered. But in prayer he heard the answer: “No, but when you were in solitude and there was no one else it was God who was your helper. Now that you are in the world, it is man.”

Solitude did not, however, guarantee peace or spiritual progress, opening instead a new, higher but rigorous plane. The aforementioned Theodore of Pherme was once consulted by a hermit brother who was troubled in his solitude. Theodore advised him to try returning to coenobitic life for the sake of humility and obedience. But the brother returned and confessed that he was no more at peace with others as when alone. A conversation ensured, with Theodore asking the young brother:

“If you are not at peace whether alone or with others, why have you become a monk? Is it not to suffer trials? Tell me how many years you have worn the habit.”

He replied, “For 8 years.”

Then the old man said to him, “I have worn the habit 70 years, and on no day have I found peace. Do you expect to obtain peace in 8 years?”

The anecdote concludes by saying that the young brother went away encouraged.

The same struggle beset the famous Macarius the Great, who in conversation with Theopemptus, said:

“See how many years I have lived as an ascetic, and am praised by all, and though I am old, the spirit of fornication troubles me.” Theopemptus said, “Believe me, abba, it is the same with me.”

These anecdotes are no mere tales to assuage the conscience of a young hermit. The term fornication eventually came to define a specific carnal behavior but in the context of the desert hermits it refers generally to acts of the flesh, hence the opposite of the asceticism referred to by Macarius. While solitude did not eliminate temptation, it eliminated a panoply of easy provocations, leaving to one’s own self the uncontrolled thoughts, the constant vigilance against laxity, the bouts of discouragement, the lack of confidence in the path — the last what Buddhism calls “lack of faith.”

Poemen recommends flight from sensuous things. The instruments of asceticism are poverty, hardship, austerity and fasting, he tells us — “the instruments of the solitary life.” But sensuousness in the broad spiritual sense here described is provoked by human beings and their presence, and their “baggage.” Solitude, especially for the novice hermit, must be thorough-going.

Several anecdotes tell of desert fathers who eluded well-meaning visitors — Moses, Longinus, Arsenius — by deliberately diverting their visitors about the whereabouts or identity of the hermits they sought. Arsenius explained the paramount need for solitude with a real-world analogy: A maiden hidden in her father’s house has many suitors, but once she is married and about in the world she is no longer the object of desire, only, perhaps, of gossip. Likewise, the soul when hidden retains its attractiveness, but once it goes out into the world it is common and like every other soul.

Ultimately, as Abba Moses says, the solitary must die to his neighbor and to the things of this world, must die to everything before leaving the body. This is the attitude of the Hindu sadhu and the special emphasis of the Buddhist teacher Buddhaghosa. Only in this way does the solitary neither injure another, nor find another a provocation to what the hermits call fornication.

In solitude is spiritual integrity. The solitary must see other people with what Abba Peter described as “the frame of mind as when you have met a stranger on the first day that you met them, so as to not become too familiar with them.” For familiarity with others is like “a strong burning wind. Each time it arises everything flies swept before it, and it destroys the fruit of the trees.”

The psychology of the Desert Fathers and Mothers remains fresh and clear even today, and remarkably relevant regardless of one’s religious or spiritual disposition. The solitude these hermits envision, the safeguards they plan, the pitfalls they foresee, are universal. No one aspiring to solitude can ignore the insights of the desert hermits.

¶

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

Quotations from Sayings of the Desert Fathers, translated by Benedicta Ward (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1987) and The Desert Fathers, translated by Helen Waddell (New York: Vintage, 1998; Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1957).

URL of this page: http://www.hermitary.com/solitude/desert.html

© 2004, the hermitary and Meng-hu

LOVE

He who persists ceaselessly in prayer must not disparage the man incapable of doing this, nor must the man who devotes himself to serving the needs of the community complain about those dedicated to prayer. For if the prayers and the service are offered in the spirit of simplicity and love for others, the superabundnce of those dedicated to prayer will make up for the insufficiency of those who serve and vice versa. ~ St. Makarios of Egypt

When we pray, let our aim be this mystery of deification – which shows us what we once were like, and what the self-emptying of the only begotten Son through the flesh – has now made us. ~ St. Maximos, the Confessor

Virtues are formed by prayer. Prayer preserves temperance. Prayer suppresses anger. Prayer prevents emotions of pride and envy. Prayer draws into the soul the Holy Spirit, and raises man to Heaven. ~St. Ephraim of Syria

Stillness, prayer, love and self-control are a 4-horse chariot bearing the intellect to heaven. ~ St. Thalassios, the Libyan

If you are seated and see that prayer is active in your heart, do not abandon it to rise for psalmody until, in God’s good time, it leaves you of its own accord. Abandoning the interior presence of God, you will address yourself to Him from without, thus passing from a higher to a lower state, provoking unrest and disrupting the intellect’s serenity ~St. Gregory of Sinai

Those not yet capable of persisting in prayer can easily grow arrogant, thus allowing the machinations of evil to destroy the good work in which they are engaged, making a present of it to the devil. Unless humility and love, simplicity and goodness regulate our prayer, the pretense of prayer cannot profit us.~ St. Markios of Egypt

Whether you are in church, or in your house, or in the country; whether you are guarding sheep, or constructing buildings, or present at drinking parties, do not stop praying. When you are able, bend your knees, when you cannot, make intercession in your mind, ‘at evening and at morning and at midday.’ If prayer precedes your work and if, when you rise from your bed, your first movements are accompanied by prayer, sin can find no entrance to attack your soul. ~ St. Ephraim, The Syrian

Spiritual knowledge comes through prayer, deep stillness, and complete detachment, while wisdom comes through humble meditation on Holy Scripture and above all, through grace given by God. ~St. Diadochos of Photiki

The Desert Fathers on Love http://www.benedictinesofheartsonghermitage.org/custom4_1.htm

What is Monasticism?

(by H.H. Coptic Pope Shenouda, III)

What is Monasticism, as it was founded and blossomed in the early centuries?

Yes, what is the Monasticism that attracted many tourists to Egypt just to see our fathers in the desert and hear a word of wisdom from their mouths; or learn some lessons from their fathers’ lives?

Yes, what is the Monasticism that our holy fathers lived and which Paladius, Rofinus, and John Cassian wrote about? And who is Saint Athanasius that explained a version in his book about St. Antony?

Monasticism is not only a name – or a monastery legacy. It does not reside in the monks’ clothes – nor is it attached to their kolonsowa (head garment) or their belts.

Monasticism is living a life of inner liberation – from materialism.

Our fathers have lived angelic lives. It is said that monks are earthly angels and heavenly humans. They are people who have deprived themselves of everything, to live humbly, and in contemplation in its highest level, executing the word of the Holy Bible.

“Do not love the world or the things in the world” (1 John 2:15-17).

“When He had made a whip of cords, He drove them all out of the temple, with the sheep and the oxen, and poured out the changers’ money and overturned the tables. And He said to those who sold doves, “Take these things away! Do not make My Father’s house a house of merchandise!” Then His disciples remembered that it was written, “Zeal for Your house has eaten Me up.” (John 2:15,17)

Accordingly, monks rid themselves of all the worldly desires – such as money, material things, positions, or fame. They leave everything on earth – so that God may be their world.

Monks no longer desire worldly ways or their positions, but they choose poverty exactly like their hero, St. Antony fulfilled the word of the Bible: “If you want to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have a treasure in heaven; and come follow Me (Matthew 19:21). So, he went and gave away all of his possessions to the needy, before he began his monastic life, and he lived as a poor monk in an ascetic life.

It is true – that monasticism and wealth are complete opposites – which cannot travel in the same path of life. It is also true that monasticism and luxury do not correlate, because luxury is an easy way of life, to which poor people, other than monks, are not exposed to.

Monks leave the world to live in the desert, mountains, and caves – in order to live with God. The God they have dedicated their lives to.

How deep is the everlasting expression which identifies monasticism!

Monasticism is a total withdrawal from every person and every material thing to connect to the One and Only “God”, Who fills the heart, mind, and time. A monk will never achieve this spiritual level, if he still desires worldly things. Here we remember what Jesus Christ said to Martha, “Martha, Martha, you are worried and troubled about many things. But one thing is needed and Mary has chosen that better part, which will not be taken away from her.” (Luke 10:41-42).

The goal of true monasticism is a continuous life filled with prayers.

A life of continuous prayer – is the main feature of a monk’s life, which ordinary people cannot live because of their worldly engaging tasks and interests.

He who begins a monastic life trains himself to a continuous life of prayer. When he succeeds, he then begins a life of isolation, which then helps him in his prayers and contemplation.

This is why monasticism is a life of loneliness.

From loneliness originated the name of the monk. The word in Greek (monakes) means lonely. In French, “moine” means a monk. In English…etc. In loneliness a monk may continue a life of prayer, contemplation, and songs without delay or distraction of any kind.

A true monk escapes people to be with God.

This is what St. Arsanius the Great had done. St. Macarius of Alexandria once asked him saying, “Father why do you flee from us?” He answered saying, “The Lord knows that I love you all, but I cannot speak with God and people at the same time.’

This is why the Spiritual Elder in his deep wonder expression once said,

“The love of God made me a stranger to humans and their ways.”

Desert Religious Art Expressed in Icons and Frescoes

Icon of Christ As Pantocrator

Jesus Christ as “Pantocrator,” meaning “Almighty, All-Powerful,” is the ancient Greek word used by St. Paul to describe the Lord in 2 Corinthians 6:18. And also used by St. John 9 times in the Book of Revelation: 1:8; 4:8; 11:17; 15:3; 16:7; 16:14; 19:6; 19:15 and 21:22.

This is the oldest known painting of Jesus of Nazareth.

It was once dated to the 1200’s, but after it was cleaned in 1962 and the original encaustic layer exposed, it was re-dated to the 500‘s under the reign of Emperor Justinian (527-565AD).

Justinian had founded St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mt. Sinai, Egypt and it was under his reign that this type of religious iconography was first created.

Encaustic (from the Greek word “enkaustikos” meaning “to burn in”) painting is also known as hot wax painting—heated beeswax to which colored pigments are added and then applied to a surface. Encautic painting with wax, hot or cold, as a medium goes back thousands of years.

Dioscorides (40-90 AD), in De Materia Medica 2.105 describes how the cold Punic Wax used in painting was made.

The Greek mummy portraits found at Fayum in Egypt, dating to the late centuries BC, early centuries AD are breathtaking examples of the Punic Wax technique.

As can be seen from the young ages of the many mummies, life was brief in the ages before modern medicine.

There is another famous mosaic of the Pantocrator in the Hagia Sophia, once a church, then a mosque and now a museum, in Istanbul, Turkey. The mosaic was done in the 1260’s and the resemblance to the 500’s Pantocrator is uncanny, leading some to believe that the artist had seen or had access to the St. Catherine painting done 700 years previously.—Sandra Sweeny Silver

St. Catherine's Monastery, Sinai.................Jesus Pantocrator.............Emp Constantine + Justinian in Hagia Sophia

A Prayer From the Desert – Part I

“Lord Jesus Christ, whose Will all things obey: pardon what I have done; grant that I, a sinner, may sin no more! Lord, I believe that though I do not deserve it, You can cleanse me from all my sins. Lord, I know that man looks upon the face, but You see the heart. Send Your Spirit into my inmost being, to take possession of my soul and body. Without You I cannot be saved; with You to protect me, I may long for Your Heaven. Now I ask for Your salvation. I ask You for wisdom, deign of Your great goodness to help and defend me. Guide my heart, Almighty God, that I may remember Your Presence day and night. ++ Amen ++

Widely known as the “bustan al-rohbaan” (The Monks’ Garden) in the Coptic Catholic Church, is not a single book, rather a collec- tion of sayings and stories written by and of the Desert Fathers of Egypt. These are from a book edited by Sister Dr. Benedicta Ward, SLG of Sisters of the Love of God at Incarnation Monastery in Oxford, England.

In the 4th Century AD, an intensive experiment in Christian living began to flourish in Egypt, Syria and Palestine. It was something new in the Christian experience, uniting the ancient forms of monastic life with the Gospel. West of the Nile Delta was the Nitrian Desert, a wasteland, a dry lake area which only contributed salts for embalming the dead. In Egypt this solitary movement was so pop- ular that both the civil authorities and the monks themselves became anxious. As for the officials of the Empire, so many thousands were following a way of life that excluded both military service and payment of taxes, but also the monks, as the large number of inter- ested tourists threatened their solitude.

The first Christian monks tried every kind of experiment with the way they lived and prayed, but there were 3 main forms of monastic life: there were the hermits who lived alone; there were monks and nuns living in communities; and in Nitria and Scetis there were those who lived solitary lives, but in groups of 3 or 4, often as disciples of a master. For the most part they were simple people, peas- ants from the villages alongside the Nile, though a few were well educated.

“A beginner, who goes from one monastery to another, is like a wild animal who jumps this way and that for fear of the halter.”

Visitors, who were impressed and moved by the penitential life of the monks, imitated their way of life as far as they could, and also provided a literature that explained and analyzed this way of life for those outside it. However, the primary written accounts of the monks of Egypt are not these, but records of their words and actions by their close disciples. Often, the first thing that struck those who heard about the Desert Fathers was the negative aspect of their lives. They were humble people who did without: not much sleep, no baths, poor food, precious little water or company, ragged clothes, hard work, no leisure, absolutely no sex, even in some places, no church either – a dramatic contrast of immediate interest to those who lived out the Gospel differently.

But to read their own writings is to form a rather different opinion. Although the literature produced among the monks them- selves is not very sophisticated; it comes from the desert, from the place where the amenities of civilization were at their lowest point, where there was nothing to mark a contrast in lifestyles; and the emphasis was less on what was lacking, but more on what was present. The outsider saw the negations; disciples who encountered the monks through their own words and actions found, indeed, great austeri- ty and poverty, but it was neither unbelievable nor complicated. These were simple, practical people, not given either to mysticism or to theology, living solely by the Word of God, for the love of the brethren and of all creation, waiting for the coming of the Kingdom with eager expectation, using each moment as a step in their pilgrimage of the heart towards Christ.

From this deep desire for the Kingdom of Heaven came power to dominate their whole lives so that they lived without things: they kept silence, for instance, not because of a proud and austere preference for aloneness, but because they were learning to listen to some- thing more interesting than the talk of men, that is, the Word of God. These were rebels, the ones who broke the rules of the world – which say that property and goods are essential for life, that the one who accepts the direction of another is not free, that no one can be fully human without sex and domesticity. Their name itself, anchorites, means rule-breakers, the ones who do not fulfill their public duties. In the solitude of the desert they found themselves able to live in a way that was hard but simple, as true Children of God.

Abba Milos of Belos said, “Obedience responds to obedience. When someone obeys God, then God obeys his request.”

|

|

The literature they have left behind is full of a good, perceptive wisdom, from a clear, unassuming angle. They did not write much, most of them remained illiterate; but they asked each other for a “word,” that is, to say something to recognize the Word of God, which gives life to the soul. It is not a literature of words that analyze and sort out personal worries, or solve theological

problems; nor is it a mystical literature concerned about presenting prayers and praise to God in a direct line of vision; rather,

it is oblique, unformed, occasional, like sunlight glancing off a rare oasis in the sands.

Abba Antony said, “Our life and our death are with our neighbor. If we gain our brother, we have gained our God; but if we scandalize our brother, we have sinned against Christ.”

Abba Nilus said, “The arrows of the enemy cannot touch one who loves silence; but he who moves about in a crowd will often be wounded.”

–Sister Dr. Benedicta Ward, SLG

|

|

PART 2 Follows.